Peering into North Korea

The key to our speedboat turned, the engine roared and Chinese pop music blared. Beneath us, the Yalu River was a muddy brown; above, the sun shone. We hurried on toward our destination: Sinuiji, North Korea.

The boat would not allow us to dock at North Korea. Legally, we could not set foot on the soil. We would, however, get within three or four metres of the banks of the border city Sinuiji. From that vantage point, we could peer inside this secretive state – without the tricky paperwork, background checks and formalities of an on-the-ground tour.

The journey to Sinuiji started in the Chinese border city of Dandong, reachable by overnight train from Beijing. Dandong stands on the banks of the Yalu River, with only a few hundred metres of water in some places between it and Sinuiji, where around 250,000 people are thought to live. Home to about 750,000 residents, Dandong is full of bustling cafes, bars and stalls selling imports like North Korean cigarettes and coins. But in the summer, the city crowds with tourists, all drawn by one thing: the chance to get a glimpse of North Korea. When I booked my waterfront hotel, the Crown Plaza Dandong, I even had the option of paying for an upgraded room with a view of the North Korean landscape.

North Korea’s green mountains rise just across the water. Unlike in Dandong, there are no high rise buildings and little activity can be seen. In fact, the highest manmade object in view is a Ferris wheel. Locals say they’ve never seen the ride in use; it just appeared one day, in what seems to be an unusual display of prosperity.

The ruins of the China-North Korea Friendship Bridge extend across the Yalu River, built in 1911 to celebrate the alliance between China and North Korea but destroyed by the Americans in the Korean War. Today, the bridge is a tourist attraction. For 30 yuan, you can walk the bridge to halfway across the river, where damaged concrete foundations lie abandoned in the water. Directly across on the North Korean banks stands a large white waterslide – never in use, but a strangely recent addition that was built within the last year. With binoculars, you can just make out a few people walking on the banks. Travellers pose for photos by a North Korean flag at the bridge’s Chinese-side base, the North Korean landscape in the background.

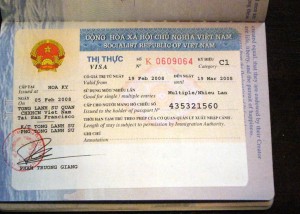

Nearby, a separate, working bridge connects China and North Korea, but is heavily guarded. Few vehicles travel between the two countries every day; occasionally, a small bus with Chinese tourists passes through. Most tourists, however, cannot take the bus across the border – and even for those who can, getting permission is a headache of paperwork and bureaucracy.

And so, instead, I took a boat: the only way to get as close as possible to North Korea, without physically entering the country. Avoiding the touts who heckle tourists in the street, I hired a boat from one of the numbered jetties. In a motorboat of about 30 other curious travellers we crossed the river, weaving past a mix of Chinese and North Korean boats anchored in the water.

As we approached the North Korean banks, the area looked like a waterfront ghost town. Some locals sat by houses; others were digging by the waterslide with small tools. A young girl in red shoes ran past her mother – the only person I saw moving with any kind of speed.

As we continued along the shore, one man waved slowly from a small, rusty boat yard. As the boat moved north, I could see white Japanese-style houses. Outside, some people bathed in the muddy water, armed guards watching. Soldiers were stationed in small huts; others marched, patrolling the banks. Even the soldiers, like the residents, looked small and thin.

As our tour continued, I could see other details: a small school with a broken window, a dusty path along the riverbank. The tallest building I could see reached no more than two stories. As I looked back, the contrast to busy Dandong was stark.

At night, Dandong lit with glowing neon colours. People filled the bars and cafés. The darkness on the other side of the Yalu made it look as if there was nothing there. Yet silently, North Korea looked on.